Judi – Founder

Judi brought CRS to life back in 1992. She had a background in social work and had worked closely with Pacifica and migrant background people, and had also worked for Child Youth and Family, as well as being involved with ESOL teaching. At the time, a lot of resettlement in Christchurch had been done by North West churches as a lot of Cambodian refugees entered the country. But the people behind this work were getting into their seventies, and the need for support for refugee and migrant background people was increasing. Through her ESOL teaching, Judi met refugee and migrant background families, and realised there was a demand to support these people settle into Christchurch.

Prior to the nineties, all resettlement in New Zealand had been done by the Inter Church Commission Refugees (ICCR); there was no government agency to support refugees and migrants at the time. Judi slowly started to meet some of these families through her teaching, and one day had Anne Marie Reynolds turn up at her door. Anne Marie was a Refugee Services Coordinator at the time for Refugee and Migrant Service (RMS), responsible for resettlement of the whole of the South Island. Judi says, “She changed my life. She was amazing.”

Judi says at the time, there were multiple small community groups dotted around Christchurch working in resettlement.

“All of these groups pulled together to help CRS become what it is. There were all little groups of people doing amazing things, but they didn’t know about each other, I didn’t know who they were, they didn’t know who I was.”

Judi says part of the beginning of setting up what became CRS was “to find what those pillars were. To build an organisation, you have to have really good foundations.” Over the next few years, Judi set about finding and establishing those foundations.

Judi talks about CRS as being like a puzzle, with multiple puzzle pieces going into building CRS. She says the first piece of that puzzle was Anne Marie, RMS and the North West Churches. Another piece of the puzzle was the Papanui Baptist Church, who had been sponsoring some Khmer families. The community groups and the people that Judi met along the way slotted into this puzzle.

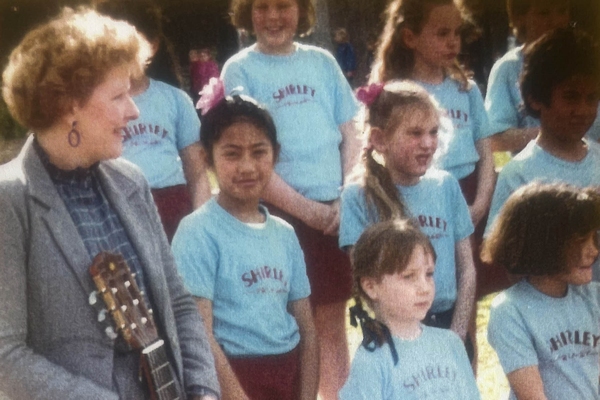

Through Judi’s work as an ESOL teacher, she began to meet refugee families. She met families who had come from traumatic backgrounds, families who were illiterate and lacking in support in the home. She saw the need to provide support to these families in order to have them participate in the school communities. Judi explains that during the nineties, Tomorrows Schools was a partnership between schools and communities that helped to engage parents in the learning of their children. This organisation struck a chord with Judi, who saw the need to help parents of refugee and migrant backgrounds engage with their children’s learning. Judi then went to an ESOL conference in Auckland, where she heard former refugees speaking about their experiences. It was here that Judi realised the need for support around mental health, as families adjusted to living with trauma as well as adjusting to life in a new country. She says, “What we know about resettlement, if there isn’t robust support that is not patronising, or taking over but empowering them, walking that journey, that resettlement for a lot of people can be very lonely.”

Judi returned from this conference and began to write a proposal. The principal of the school gave her a room in the school to work from, and it was here that she created a space for refugee parents and children to come together and connect. Judi then met Hyang, who was the first Cambodian interpreter that was employed. The pair of them set up English language classes, as well as classes to support parents in learning other skills, such as sewing or the Road Code. Judi then went about finding other people to join the team, creating a network of people who formed the bones of what would later become CRS.

Judi says for her, forming CRS wasn’t a project, it was a calling.

“Once it gets into your heart there was just nothing else on the radar, it was very powerful in that something bigger than yourself that you could never do by yourself, but you knew that if it could work it could actually just bless and help so many people.”

Judi says highlights for her include the people she met along the way, including the people who helped shape CRS and who gave up their time to help build the agency from the ground up, as well as the families, who she says, she still thinks about often. “Sometimes I bang into them, it’s like long lost family.”

When Judi started her work, at the time there was only one professional organisation in New Zealand that supported refugees. This was Refugee as Survivors (RAS) in Wellington. CRS became the first social service for refugees in New Zealand. “That is a highlight for me, that is a huge achievement that something exists that never existed before,” she says. “That, and the fact it still exists.”

Judi was asked, “How does it feel to know that the agency is 30 years old?” She replied, “I’d say that there has to be some very dedicated people in that organisation. I have the greatest respect for the General Manager, I think she has carried that baton faithfully, her heart is with the families. I would say that Christchurch is very fortunate, Canterbury is very fortunate. There are lots of places in the world, they don’t have a dedicated social service, they might have a centre where there’s a whole lot of people that they can go to but there’s only one person there that has any connection with refugee resettlement, they’re sort of more generic, so CRS is quite a unique organisation.” Judi’s dedication to her work has seen her travel the world and meet many different people. She says, “One of the most profound things I did, I was in Chicago at one of the Refugee Highway Partnership meetings, I went to the Holocaust Museum, that’s got all the stuff from the Cambodian killing fields. It was so shocking and profound and when I came out I just thought, I said thank you Lord that, I couldn’t stop that, I couldn’t change that, but for the people that survived that, You brought them to us, and that responsibility to help heal and help them recover is a very high calling. You feel so powerless, but even if it was just one child or one family, you know you’ve made a different kind of imprint.”